Horizontal audit on Indigenous employment in the banking and financial sector

This first sector-wide employment equity report uses findings based on the Commission’s new horizontal audit model. While there has been some progress in increasing the representation of designated group members across the sector, there has been little to no progress in the representation of Indigenous people. This audit looked at compliance with the Employment Equity Act, identified employment barriers faced by Indigenous people within the banking and financial sector, and gathered best practices to share with employers in the sector to assist them in the recruitment and retention of Indigenous people in their workforces.

Executive Summary

In 2018, the Canadian Human Rights Commission began using a new horizontal audit model to better serve and support employers looking for guidance on how to comply with the Employment Equity Act (EEA). The new horizontal audit model focuses on systemic issues faced by members of the four designated groups. The ultimate goal of the horizontal audit is to examine why women, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities and racialized groupsFootnote 1 still face barriers to equitable representation in the federally-regulated workforces. The new approach also includes a gender-based lens to capture experiences of women across designated groups, and a diversity and leadership lens to promote a higher representation of designated group members in management roles. Each horizontal audit takes an in-depth look at the representation and advancement of a specific designated group in a specific sector.

This is the first sector-wide employment equity report that uses findings based on the Commission’s new horizontal audit model. This first audit looked at Indigenous employment in Canada’s banking and financial sector. With approximately 240,000 employees across the country, this sector has a key role to play in promoting workplace equality. Since 1997, the Commission has conducted almost 80 employment equity audits/assessments in the banking and financial sector and has monitored progress to ensure compliance with the EEA. While there has been some progress in increasing the representation of designated group members across the sector, there has been little to no progress in the representation of Indigenous people.

This horizontal audit looked at compliance with the EEA, identified employment barriers faced by Indigenous people within the banking and financial sector, and gathered best practices to share with employers in the sector to assist them in the recruitment and retention of Indigenous people in their workforces.

Thirty-six employers completed the employment equity survey. From there, ten employers were selected to participate in the second phase of the audit, which consisted of a full assessment of their employment equity program with respect to Indigenous employment.

The horizontal audit found that:

- 40% of the employers identified barriers in their hiring practices for Indigenous women and men, and have implemented measures to eliminate them.

- The top employment barriers identified are related to recruitment strategy selection processes and the lack of Indigenous role models and/or mentors in the banking and financial sector.

- While 82.9% of the employers have an employment equity committee, only 34.3% have an Indigenous representative on their committee. Similarly, only 11.4% have an Indigenous representative from management on the committee.

- 45.7% of the employers reported addressing all or the majority of barriers in their employment equity plans, while 28.6% reported addressing none or a few.

- 62.9% of the employers reported incorporating their employment equity goals in their succession planning process. At the same time, only 25.7% of these employers identified Indigenous men for management or other key positions in their organization and only 14.3% identified Indigenous women for the same type of positions.

The overall findings confirm that there is still a gap in employment opportunities and employment practices when it comes to Indigenous representation in Canada’s banking and financial sector.

But that gap can be closed. The audit uncovered promising practices that all employers in Canada, not just in the banking and financial sector, can use to attract or retain Indigenous employees. These promising practices include: an application screening process that takes into consideration lived-experience or career gaps; anti-harassment training for managers and employees; wider advertising of all opportunities (including senior management positions) throughout the organization; and putting robust anti-discrimination/anti-harassment policies into place.

Everyone in Canada will benefit when all Canadians have the opportunity to be active participants and to contribute in our workforce and our economy. This new horizontal audit model is a trusted tool that the Commission will continue to use to promote the inclusion and equal participation of all members of the designated groups across Canada’s workforce.

Introduction

The purpose of the Employment Equity Act (EEA) “is to achieve equality in the workplace so that no person shall be denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to ability and, in the fulfilment of that goal, to correct the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minoritiesFootnote 2 by giving effect to the principle that employment equity means more than treating persons in the same way but also requires special measures and the accommodation of differences.”

There are nine legislative requirements under the EEA:

- Collection of workforce information

- Workforce analysis

- Employment Systems Review

- Employment Equity plan (EE plan)

- Implementation and monitoring of EE plan

- Periodic review and revision of EE plan

- Information about employment equity

- Consultation & collaboration

- Employment equity records

Under the EEA, the role and responsibility of the Canadian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) is to conduct compliance audits of federally-regulated organizations.

Employment equity – A new approach

Since 1997, the Commission has conducted many conventional audits with medium-sized and large employers (more than 500 employees) representing about 90% of employees covered by the EEA. Since that time, the Commission has observed slight overall progress in representation of Indigenous people and very little progress in the representation of persons with disabilities across the federally regulated private sector. In addition, the overall representation for women has declined, while it increased significantly for members of racialized groups. This led the Commission to believe that the conventional audit process had possibly reached its maximum impact. Many employers urged the Commission to publish some of the audits’ findings in order to share trends, identify barriers and promote best practices.

The Commission has therefore decided to modernize the way it supports employers by introducing a new horizontal audit model. This model will provide employers with guidance on how to comply with the requirements of the EEA as well as leading practices that will help to ensure better representation for members of the four designated groups.

This new model focuses on systemic issues faced by designated group members. Each horizontal audit will include a gender-based lens to better understand the situations and experiences of women across designated groups. It will also include a diversity and leadership lens to promote a higher representation of designated group members in management. This model takes an indepth look at the representation/advancement of a specific designated group in a sector.

More specifically, this new horizontal audit model will:

- address persistent representation gaps for a designated group in particular sectors;

- ensure employers have adequate plans to correct under-representation;

- identify specific barriers that impede progress;

- gather best practices and proven special measures that increase representation and help retain employees; and

- share best practices and proven special measures with employers through the publication of sector-wide reports

Horizontal audit on Indigenous employment in the banking and financial sector

Canada’s banking and financial sector has a key role to play in promoting workplace equality, with approximately 240,000 employees across the country. Since 1997, the Commission has conducted almost 80 employment equity audits in the banking and financial sector and has monitored progress to ensure compliance with the EEA. While there has been some progress in increasing the representation of designated group members across the sector, there as been little to no progress in the representation of Indigenous people.

Within this context and in light of the national commitment toward reconciliation, the Commission has decided to conduct a sector-wide horizontal audit on Indigenous employment within the banking and financial sector. The main objectives of the audit are to:

- assess compliance with the EEA;

- identify employment barriers faced by Indigenous people within the banking and financial sector; and

- gather best practices to share with employers in the sector to assist them in the recruitment and retention of Indigenous people in their workforces.

The audit looked at the following four areas:

- How well the employer is doing at ensuring the success of their EE program.

- How well the employer understands the specific employment barriers that are facing Indigenous people in their organization.

- How well the employer is doing at improving and demonstrating representation of Indigenous people in their organization, including an evidence-based action plan with measurable goals.

- How well the employer is promoting and improving the representation of Indigenous people in leadership/management positions.

Methodology

The Commission applied a rigorous methodology process during this horizontal audit. In 2018, an audit survey was sent to employers in the banking and financial sector who submitted their respective annual employment equity results to the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). The objective of the audit survey was to determine what measures each employer has taken to identify barriers to employment and to increase the representation of Indigenous people in their organization.

The survey was also used to randomly select a total of ten employers for the next step of the audit, which consisted of a full assessment of their employment equity program with respect to Indigenous employment. Each of the 10 selected employers received a formal notification letter with a Submission Index in which they had to list and send the supporting documentation they deemed necessary to demonstrate achievement of the objectives that correspond to each line of inquiry.

The Commission auditors then arranged on-site visits to conduct in-person interviews with various employees in the organizations. In order to have a comprehensive picture of each organization’s reality, interviews were held with senior managers, hiring managers, human resources representatives or specialists, members of the diversity or inclusion committee, and Indigenous employees. Each person interviewed answered a series of questions related to employment equity and Indigenous employment in their workplace. Questions varied based on the position and role of the employee. The Commission then compared the evidence collected during the interviews with the initial data the employers provided in the Submission Index.

The following section of this report presents the main results of the audit survey. The second section summarizes the main finding of the horizontal audit in relation to the lines of inquiry. Then Annex A outlines recommendations on how to remove employment barriers for Indigenous people identified during the horizontal audit exercise.

Section one: Sector-wide survey results

The Commission sent an audit survey to employers in the banking and financial sector who submitted their respective annual employment equity results to the Labour Program of ESDC.

The survey consisted of six themes:

- knowing their workforce

- understanding employment barriers for Indigenous people

- addressing employment barriers

- adopting a diversity leadership approach to Indigenous employment

- promising practices

- accountability and monitoring

Theme one: Knowing your workforce

Employment equity seeks to correct under-representation of the designated groups in an organization’s workforce. To measure workplace representation, employers have to determine the percentage of each designated group by occupational group in their organization. The most trusted tool to collect this data remains the self-identification survey, wherein employees are asked to self-identify as belonging to one or more of the four designated groups. The results are then used to construct the workforce analysis, to focus the Employment Systems Review (ESR), and to provide a rationale for the initiatives in the EE Plan.

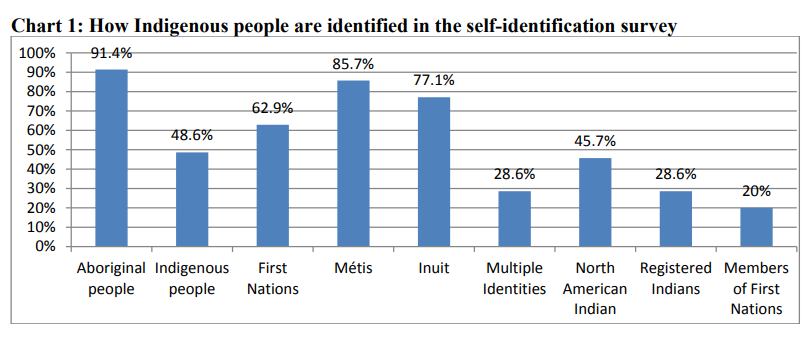

The EEA defines ‘‘Aboriginal peoples’’ as persons who are Indian, Inuit or Métis. The Commission recognizes that the terms “First Nations” and “Indigenous” are increasingly replacing the terms “Indian” and “Aboriginal”. The Commission encourages employers to update their self-identification forms. Having an updated EE self-identification survey that reflects the current picture of Indigenous identities might encourage Indigenous employees to self-identify. As seen in chart 1, the Commission found that employers in the banking and financial sector use a variety of terms to designate Indigenous people. More than 75% of employers referred to Aboriginal people (91.4%), Métis (85.7%) and Inuit (77.1%) in their self-identification definitions. Approximately 60% reported using the term First Nations, while more than 40% are using Indigenous people (48.6%) and North American Indian (45.7%). Only 28.6% used the terms Multiple identities and Registered Indians, while one out of five used Members of First Nations on their self-identification survey.

Chart 1: How Indigenous people are identified in the self-identification survey

Chart 1: Text version

| Identification | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Aboriginal people | 91.4% |

| Indigenous people | 48.6% |

| First Nations | 62.9% |

| Métis | 85.7% |

| Inuit | 77.1% |

| Multiple Identities | 28.6% |

| North American Indian | 45.7% |

| Registered Indians | 28.6% |

| Members of First Nations | 20% |

In their response to the survey, a total of 40% of employers reported that their last organizationwide self-identification survey was conducted less than a year ago, while 20% reported that it was more than four years ago. Return rates varied between 70% and 100%. All audit survey participants had a process in place to ensure that new employees were surveyed and 80% had a follow-up strategy for unreturned survey forms. In relation to Indigenous employees, 42.9% of audit survey employers had a communication strategy to promote Indigenous participation in their self-identification surveys and 34.3% had an ongoing approach to promote Indigenous selfidentification.

Sharing the Work Force Analysis results

The Workforce Analysis (WFA) shows the levels of representation of each designated group in each of the EE occupational groups in an organization’s workforce. These levels of representation are compared to census data to determine the existence and degree of underrepresentation of any designated group in any occupational group. The WFA should also be regularly updated and shared with managers to ensure they are aware of gaps in representation when they initiate hiring processes. Approximately 90% of survey participants reported having communicated the results of the WFA to their managers.

Employment equity committee

An EE committee is a convenient way for employers to better know their workforce, and also to meet the EEA requirements to consult and collaborate with their employees’ representatives. The Commission recommends that the committee include both management and non-management members, members from different business lines, occupational groups, geographic locations, and members from each of the four designated groups.

The main purpose of the committee is to assist in the preparation, implementation, and revision of the organization’s EE plan. EE committees, acting as advisory groups, can be a valuable resource in communicating EE information to the workforce, helping to identify employment barriers, suggesting referral sources, and designing special measures for under-represented designated groups. Having a representative from each designated group ensures that each group has a voice in committee discussions. Among the employers surveyed, 82.9% have an EE committee, but only 34.3% have an Indigenous representative and only 11.4% have an Indigenous representative from management on the committee.

Theme two: Understanding employment barriers for Indigenous people

The ultimate goal of EE is to remove employment barriers for the four designated groups and close any gaps in representation. The barriers will vary by designated group, by occupational group, and by workplace. Therefore, in order to effectively remove barriers and design programs/strategies to attract and retain employees from the four designated groups, employers need accurate knowledge of the specific difficulties and barriers people within their organization are facing.

Employment Systems Review (ESR)

The ESR is a tool to help diagnose why a particular designated group is under-represented in a specific occupational group. It is based on the WFA results and the flow data results. In other words, it is based on a picture of the under-representation of designated groups at a recent point in time, as well as the organizational history of hiring, promoting, and terminating practices for members of these groups. The WFA/flow data indicate the areas to be examined; and the ESR is the concluding report on the examination of these areas.

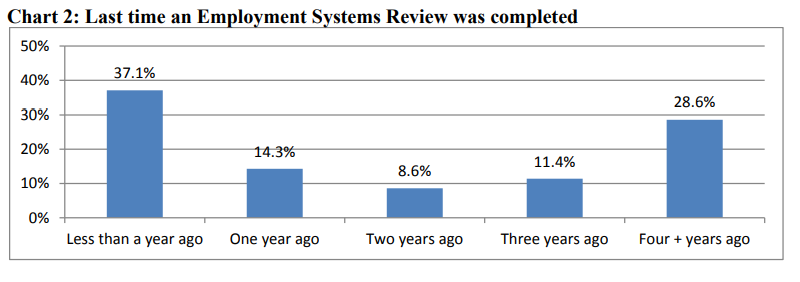

A thorough ESR always involves direct consultation with members of the under-represented designated groups. The Commission recommends employers undertake an ESR every three years to ensure they are well aware of any new employment barriers. As seen in Chart 2, 37.1% of employers reported having completed an ESR within the last year, while 28.6% reported an ESR that was four years or older. However, only 37.1% consulted with Indigenous employees for the ESR.

Chart 2: Last time an Employment Systems Review was completed

Chart 2: Text version

| Employment review | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than a year ago | 37.1% |

| One year ago | 14.3% |

| Two years ago | 8.6% |

| Three years ago | 11.4% |

| Four + years ago | 28.6% |

Barriers to employment for Indigenous people

A good number of employers (40%) reported that they had identified barriers to employment applying to Indigenous women, Indigenous men, or both, and had implemented measures to eliminate them. As seen in Table 1, the top barriers identified by employers are related to recruitment strategy (37.1%), selection process (22.9%), lack of Indigenous role models and/or mentors (22.9%), and promotion (20%).

Table 1: Proportion of institutions that identified barriers for both Indigenous men and women by type of barrier

| Recruitment strategy | 37.1% |

|---|---|

| Selection process | 22.9% |

| Hiring decisions | 11.4% |

| Lack of retention strategy | 11.4% |

| Access to training | 8.6% |

| Career development | 17.1% |

| Lack of mentoring | 17.1% |

| Promotion | 20% |

| Lack of Indigenous role models and/or mentors | 22.9% |

| Lack of awareness of employment equity purpose and goals | 8.6% |

| Lack of monitoring and engagement | 8.6% |

| Workplace culture | 17.1% |

| Lack of accommodation | 8.6% |

| Work-life balance | 8.6% |

| Lack of consultations with Indigenous employees | 17.1% |

Theme three: Addressing employment barriers

Employment barriers may be physical, structural, or attitudinal. A physical barrier would be steps to enter a building or lack of an elevator; a structural barrier would be a policy establishing a set level of education when that level is not required for the position; an attitudinal barrier would be seeing members of a designated group as being “less than.” Barriers often reflect an organization’s failure to keep abreast of the needs of a changing labour market or a failure to eliminate outdated policies and practices that now put members of designated groups at a disadvantage.

Employment equity plan

An EE plan is an action plan that contains measures to remove the employment barriers identified in the ESR and to correct the under-representation of designated group members. Each item in the plan has a timeline, a performance indicator and an assigned responsibility center. Audit survey results show that 88.6% of employers reported having an EE plan, with the majority of plans covering a period of two to three years. Only 17.1% of employers had an annual employment equity plan. Less than half of the employers (45.7%) said they consulted with Indigenous employees while developing the EE plan. Approximately 70% of employers reported sharing or communicating their EE plan with managers, while approximately 50% reported sharing or communicating it with their employees.

Actions and measures

The action items in an EE plan are the steps the organization will take to remove the barriers identified in the ESR and the “promising initiatives the organization will implement to create a more inclusive environment. For example, it could mean revising job qualifications so that, whenever possible, a combination of education and lived-experience would be considered. An employer might also develop and promote a policy on flexible work arrangements. In all, 45.7% of employers reported addressing all or the majority of barriers from the ESR in their EE plans, while 28.6% of employers reported addressing none or a few of the barriers from the ESR.

Special measures

Special measures are temporary initiatives an organization puts in place to hasten the closing of a gap in representation for a designated group in a particular occupational group. Examples of special measures to reduce disadvantage for Indigenous employees could include a recruitment strategy for Indigenous candidates with hiring goals for specific occupational groups. Other examples could include a special program to hire a minimum number of Indigenous interns/coop students each year, or reserving a minimum number of seats in management or other training courses for Indigenous candidates/employees.

Results from the audit show that 45.7% of employers reported that their EE plans contain special measures to increase representation of Indigenous women and Indigenous men.

Theme four: Adopting a diversity leadership approach to Indigenous employment

Succession planning

To address the under-representation of Indigenous people in middle and senior manager positions in a timely manner, organizations need to have a defined strategy with numerical goals that would cover both internal and external recruitment. Internally, it would require incorporating goals for Indigenous representation in the succession planning and management development process. Ideally, Indigenous candidates would be identified for management positions, and management development plans would be tailored to each candidate. Externally, the requirement for inclusion of Indigenous candidates in the candidate list would form part of any third-party contract or would be established as a best practice for the organization’s recruiters.

Of the employers who participated in the audit survey, 62.9% reported incorporating their EE goals in their succession planning process. At the same time, only 25.7% of these employers identified Indigenous men for management or other key positions in their organization and only 14.3% identified Indigenous women for the same type of positions. Less than a third (31.4%) of the survey participants indicated that they offered mentoring or job shadowing opportunities at the senior management level for Indigenous employees. In terms of external recruitment, 5.7% of participating employers have strategies to hire qualified Indigenous candidates at the management level from outside of the organization in their succession plan.

Commitment to Employment Equity

The successful implementation of EE in an organization depends upon the ongoing support and review of progress by senior management. To ensure senior managers are kept up-to-date on EE issues, the Commission recommends appointing a champion at the senior manager level who can make EE visible in the organization and liaise with the EE committee, employee resource groups and EE recruiters. According to the audit survey, slightly more than half (51.4%) of employers reported having a champion to increase Indigenous representation. Although more than 90% of employers reported that senior managers had formally pledged their commitment to the implementation of EE in the organization, only 34.3% of employers reported discussing EE and increasing the representation of Indigenous people monthly or quarterly. The majority of employers reported discussing EE and Indigenous representation once a year or less.

Theme five: Promising practices

Promising practices is a sector term to describe initiatives an organization has adopted that provide a supportive context for EE. These practices often benefit all employees and promote diversity/inclusion generally in the workforce. Overall, all institutions reported having promising practices in recruitment, training, promotion and retention of Indigenous people.

Survey results show that the most frequently reported promising practices in recruitment among employers are:

- job advertisements clearly outline essential job requirements (97.1%)

- application screening process takes into consideration career gaps due to family responsibilities (94.3%)

- recruitment campaigns are gender inclusive and sensitive to Indigenous cultural differences (71.4%)

- advertising promotes the vision of a diverse and gender-inclusive workforce that specifically includes Indigenous people (71.4%)

- variety of recruitment methods used to ensure a good representation of both Indigenous women and men in the applicant pool (62.9%)

The most frequently reported promising practices in training are:

- anti-harassment training for managers and employees (94.3%)

- financial support for further education/training for Indigenous employees (80%)

- unconscious bias training for managers (74.3%) and employees (60%)

- duty to accommodate training for managers (65.7%) and employees (60%)

- gender diversity training for managers (45.7%)

The most frequently reported promising practices in promotion are:

- advertisement of all opportunities (including senior management positions) throughout the organization (80%)

- transparent selection processes for promotion, with selection criteria available and accessible to everyone (74.3%)

- general availability of information on all job rotations, special assignments and opportunities for temporary senior positions (68.6%)

The most frequently reported promising practices in retention and termination are:

- anti-discrimination/anti-harassment policies in place (97.1%)

- exit interviews that clarify why Indigenous employees or managers are leaving (68.6%)

- flexible leave policy that accommodates Indigenous people’s cultural needs (60%)

Theme six: Accountability and monitoring

Implementation of EE in an organization must be managed. This means that in addition to an EE communication strategy and formal EE plan, there needs to be a monitoring/accountability strategy to ensure progress or to take corrective action. Each initiative in the EE plan should have an assignment of responsibility, a timeline, and a measurable performance indicator. The organization must also ensure it has the data collection systems in place to support assessment of performance indicators. For example, if outreach recruiting is an item in the EE plan, the organization will want to know how many contacts were made, how many referrals were received from each contact, and how many of the referrals from each contact were hired. This type of information is useful when deciding the best use of human and financial resources.

Although 65.7% of employers reported having a mechanism for monitoring the implementation of initiatives in their EE plans, only 37.1% have performance indicators for each initiative. Almost half of the employers (48.6%) reported evaluating the effectiveness of their partnerships with Indigenous organizations. EE goals for Indigenous people were included in the business plans of 37.1% of the employers. No employers reported offering incentives to managers in support of achieving Indigenous hiring targets.

Section two: Main findings by audit themes

The Commission randomly selected ten employers for a full assessment of their employment equity programs with respect to Indigenous employment. These assessments were made through an examination of supporting documentation sent by the employers and by interviews with various employees in their organizations. Four lines of inquiry were considered in determining the sufficiency of each employer’s efforts:

- enabling the EE program

- understanding employment barriers for Indigenous people

- improving representation of Indigenous people

- strengthening Indigenous leadership and performance

Line of Inquiry One: Enabling the EE program

This line of inquiry looked at how well employers are doing at taking the following steps to ensure their EE programs successfully supported the employment and retention of Indigenous people:

- defining the roles/responsibilities of senior and other managers with respect to EE

- dedicating sufficient human and financial resources to facilitate the coordination of the EE program and implement each element of the EE plan

- establishing a clear monitoring and reporting framework for the EE program

- establishing clear measures for each initiative related to Indigenous people

- evaluating the effectiveness of each measure in the EE plan

- communicating expectations and obligations to all managers and staff

The Commission looked at work descriptions of managers and those responsible for EE, internal policies relating to EE, organizational guiding documents, management performance agreements/appraisal forms, roles and responsibilities of EE champions, terms of reference for EE committees, allocation of funds in support of EE, intranet content on EE, and communication strategies to inform staff about EE.

All employers audited had staff with defined responsibilities for EE/diversity. In some cases, however, EE and diversity were not sufficiently distinguished to discern the separate obligations of EE. For example, the need for a diverse workforce was well accepted, but the need to achieve a representative workforce for Indigenous people, as well as the other designated groups, was not well understood. Because diversity has a broader scope than EE and includes other characteristics such as age, sexual orientation, and gender identity, it is possible for managers to technically achieve a “diverse” workforce even though there may be no Indigenous people among their employees.

All organizations assigned some level of resources to their EE/diversity programs, but not all assigned a sufficient level to effect a change in the representation of Indigenous people in their workforces. A few had dedicated staff to increase the recruitment and retention of Indigenous employees. One employer had a current Indigenous recruitment strategy that included data on Indigenous candidates throughout the application process, a numerical goal for increasing the overall representation of Indigenous people, and measures to reach that goal.

All of the financial institutions had an EE/diversity committee with a well-defined mandate, though not all had Indigenous committee members. Some had diversity and inclusion committees with varying degrees of responsibility for meeting EE obligations. A few had Indigenous Employee Resource Groups (ERG) with dual purposes of supporting Indigenous employees/raising internal awareness of Indigenous issues, and of reaching out to the community to attract Indigenous candidates. Those employers with Indigenous ERGs did not appear to closely consult with them on the identification of employment barriers, the development of special programs for Indigenous candidates and employees, or on recruitment/retention initiatives for Indigenous employees. Ongoing collaboration with an Indigenous ERG on such issues can add to the pool of resources available to address Indigenous under-representation.

The majority of employers audited did not have goals for Indigenous representation by occupational group as required by the EEA. Therefore, managers did not have performance objectives linked to achieving these goals and senior managers tended to receive reports only on the overall levels of Indigenous representation.

Line of Inquiry Two: Understanding employment barriers for Indigenous people

The second line of inquiry looked at how well the ten employers understand the possible barriers that Indigenous employees experience within their organization or when seeking employment at their organization. In order to assess this line of inquiry, the Commission looked at the degree to which each manager was:

- identifying the occupational groups where barriers may exist based on the workforce analysis;

- consulting with Indigenous employees to identify possible barriers with respect to:

- recruitment, training, coaching, evaluation and promotion;

- work flow and procedures;

- workplace climate and acceptance; and

- availability of accommodation.

- providing a report on the conclusions drawn from the consultations that identify barriers and to explain the proposed measures to remove the barriers.

In determining the degree to which the criteria for this line of inquiry was met, the Commission reviewed documents such as employers’ workforce analyses, records of consultations with Indigenous employees regarding employment barriers, employment systems review reports, and training materials.

Every employer submitted a recent workforce analysis that showed the gaps in representation of Indigenous people by occupational group. Employers were able to use these reports to identify significant gaps where further inquiry was warranted. In some cases, however, employers collected the data for the workforce analysis using a self-identification form that was not compliant with the Regulations to the EEA. This means some of the required information — such as the ability to identify in more than one designated group or the confidentiality of participant responses — was omitted. As well, incorrect definitions of the designated groups were sometimes used.

The key piece of evidence for demonstrating an employer’s understanding of the employment barriers Indigenous people face in their organization is the Employment System Review (ESR). An ESR includes a record of the employment policies and practices review as well as a record of the consultations with Indigenous employees about their experiences at work.

None of the organizations submitted a recent ESR report. Some organizations had no ESR, while others submitted an expired one. At the same time, however, employment barriers for Indigenous people surfaced in all of these organizations through the audit process. Some of the most frequently identified barriers were:

- lack of company visibility in Indigenous communities

- narrow range of qualifications for positions

- lack of flexibility for work-life balance

- lack of role models in senior positions

- mobility requirements within the organization, which may hinder career progression

The lack of a recent ESR should not be construed as a lack of effort to include Indigenous people in the workplace. All organizations had taken steps to create a welcoming workplace, such as introducing transparent selection processes; conducting employee feedback surveys; offering training on anti-discrimination/anti-harassment, unconscious bias, and Indigenous cultural awareness; and sponsoring Indigenous community events.

Line of Inquiry Three: Improving representation of Indigenous people

The third line of inquiry focused on an employer’s obligation to create an EE plan based on a recent workforce analysis and ESR that would improve Indigenous representation. The plan must contain numerical goals and measures to:

- remove the barriers identified in the ESR;

- create an inclusive workplace for Indigenous employees;

- accommodate the special needs of Indigenous employees;

- incorporate EE numerical goals for Indigenous employees into succession planning; and

- recruit, train, develop, promote and retain Indigenous employees in those occupational groups where they are under-represented.

The primary proof for having satisfied this line of inquiry was an up-to-date EE plan. The Commission also looked at outreach recruitment strategies, community partnerships with Indigenous organizations, and special measures to attract, develop, and retain Indigenous candidates.

Some employers had current diversity and inclusion plans, and one employer had a current EE plan. However, none of these plans were based on a recent workforce analysis and ESR, and they all lacked other essential elements. Nevertheless, employers displayed several promising practices to attract Indigenous candidates and to create inclusive work environments. As mentioned previously, a promising practice that was found was a recruitment strategy for Indigenous people that set a numerical recruitment target . The strategy also outlined a five-point action plan involving internal consultations on increasing Indigenous representation, external partnerships with Indigenous organizations, branding/communication to attract Indigenous candidates, identification of cultural competency training opportunities for recruiters, and the establishment of metrics and reports to track the effectiveness of the strategy. The metrics are used not only to check progress in meeting recruiting targets, but also to determine the return on investment of external partnerships.

Another example of a promising practice is a dedicated staff person for Indigenous recruitment who has negotiated internal partnership agreements for positions such as call centre personnel and customer service representatives. The agreements allow the Indigenous recruiter to present qualified Indigenous candidates for guaranteed hires when openings for these positions occur. Beyond the entry-level jobs, the recruiter seeks to establish long-term relationships with potential candidates, assisting these candidates through the screening and interview stages. If no suitable position is available, the recruiter maintains the relationship — sometimes over several months — while continuing to search for an opening. To optimize the placement, the recruiter works with the Indigenous employee resource group, arranging an introduction between the new placement and the chair of the resource group about two months after the start date. At the same time, the recruiter arranges for an informal Indigenous mentor and coordinates the initial contact between the new employee and the mentor.

A related positive/promising practice for external hiring is the use of a recruitment services agreement that requires contracted recruiting agencies to respect an organization’s commitment to EE by seeking out applicants from under-represented designated groups. An organization provides the contracted agency with the EE targets by designated group and occupational group, updating the information at least annually, and the agency strives to include qualified designated group members in its slate of proposed candidates. If, in any one-year period, the agency fails to supply suitable designated group candidates, it must submit a written justification stating the reasons for its lack of success. These contracts can be used for senior managers as well as for other professional or technical openings. They can also be linked to a company policy requiring a certain number or percentage of designated group candidates for positions with significant representation gaps before interviewing can begin.

A fourth promising practice that the Commission found is a well-defined corporate culture that is conveyed to all employees through a series of mandatory training modules. The majority of employees, including Indigenous employees, found this common culture to be a positive factor in their work experience. Indigenous employees commented that the culture helped them gain a sense of belonging in the organization, that it was a natural fit with their personal values, and that it was one of the first things they noticed when they joined the company. The particular values mentioned were personal accountability, treating people respectfully, being a team player, and not blaming others.

Finally, the Commission wishes to highlight support in achieving work-life balance as a positive/promising practice. This balance is especially facilitated by the accruing/granting of special leave (paid leave) which enables employees to meet their family responsibilities without using up their vacation time. The support for work-life balance is a main reason Indigenous employees decide to join an organization.

Line of Inquiry Four: Strengthening Indigenous leadership and performance

The fourth line of inquiry reviewed each organization’s process to increase the representation of Indigenous people in management positions. Employers were expected to have a formal plan encompassing the following items:

- Incorporation of EE targets for Indigenous employees into succession planning.

- Development of plans for Indigenous employees identified through the internal succession planning process to ensure their capacity to compete for management positions.

- Strategies for hiring Indigenous people externally to fill senior management roles where there is limited or no availability of internal Indigenous candidates.

The types of information assessed for this line of inquiry were documents such as descriptions and forms of organizations’ succession planning processes, sample management development plans, and data on Indigenous employees selected for management development in each establishment.

At present, none of the organizations incorporate EE targets for Indigenous people into their talent identification/succession planning processes. There are also no management development programs specifically designed or adapted for Indigenous employees. Indigenous recruitment strategies tend to have a broad focus on all positions and do not target senior management positions. None of the organizations provided evidence of having a plan to hire senior Indigenous managers externally when there are limited internal Indigenous candidates. In general, it appears that most employers have concentrated more on securing Indigenous talent for their organizations and have not yet turned their minds to attracting, developing, and retaining Indigenous senior managers.

Conclusion

Most organizations in the banking and financial sector have taken steps to create a welcoming workplace, offering training on anti-discrimination/anti-harassment, unconscious bias, and Indigenous cultural awareness. Several companies sponsor Indigenous community events or offer scholarships/bursaries to Indigenous students. Other efforts include implementing special measures for Indigenous employees, external recruiting partnerships, and dedicated staff for Indigenous recruitment.

Despite these endeavors, under-representation of Indigenous people persists in the banking and financial sector. Many organizations are not meeting their obligation under the EEA to have a current Employment Systems Review and Employment Equity Plan. Therefore, they lack a thorough understanding of the employment barriers confronting Indigenous people and do not have a plan to address those barriers. As well, only a minority of employers have strategies to recruit Indigenous people into leadership positions.

Correcting the under-representation of Indigenous people would benefit from gaining an Indigenous perspective on the issue. This could be done by consulting with Indigenous employees or by reaching out to Indigenous leadership within communities to discuss the question of under-representation and to find possible solutions to improve the situation. However, less than half of employers reported consulting with Indigenous employees in identifying employment barriers or in developing their EE plans. A minority of employers reported having Indigenous representation on the committee that monitors the EE plan. Consequently, there appears to be a lack of collaboration and/or consultation in finding solutions that would improve Indigenous representation in this sector.

Once organizations have identified employment barriers for Indigenous people and established an EE plan to address those barriers, they need to communicate their plans to recruiters, hiring managers, and senior managers. Managers must not only know where under-representation exists in the organization, but also the importance of achieving numerical targets. Thus, senior managers should regularly be updated on the achievement of Indigenous initiatives so that they can take action to ensure reasonable progress in meeting Indigenous equity goals.

In closing, the Commission hopes that these audit findings can assist the banking and financial sector to bring about equality in the workplace for Indigenous people. The findings could also inspire organizations from other employment sectors to take further action to facilitate the hiring and retention of this designated group in their workforce.

Annex A: Recommendations for removal of employment barriers for Indigenous people

Recruitment/Outreach

- Ensure your organization has good visibility in Indigenous communities so that candidates will consider your organization as a potential employer.

- Provide information on the breadth of jobs available in the banking and finance sector (e.g., positions in human resources and information technology.)

- Develop an outreach strategy that presents images and videos of Indigenous people working in banking and finance (a non-traditional sector for Indigenous people).

- Consult with Indigenous employees and Indigenous job placement agencies to find the best venues/sites for attracting Indigenous candidates. Attend Indigenous career fairs.

- Broaden the range of qualifications so that, where possible, non-business/commerce degrees are considered. Review the validity of qualifications involving set years of experience, especially when lengthy experience is requested.

- Offer summer jobs, co-op placements, and internships for Indigenous students and, where possible, transition these temporary positions into permanent ones.

Consultation with Indigenous people

- Consult with Indigenous employees to determine if any of the following barriers are present in your organization:

- lack of role models in senior positions

- differential treatment in performance expectations and acceptance of ideas

- inability to express their authentic selves at work

- lack of flexibility to achieve work/life balance

- low wages for front-line positions in relation to other available jobs

- lack of information about career paths

- Hold exit interviews with Indigenous employees and ask directly about experiences of discrimination or harassment. Ask participants to self-identify so that trends in responses can be used to discern barriers for Indigenous people.

- Establish an employee resource group for Indigenous employees. These groups can provide support to Indigenous employees, help raise awareness internally of Indigenous culture and history, and assist in reaching out to Indigenous communities.

- Consult with the employee resource group in identifying employment barriers for Indigenous people and in designing effective initiatives to increase Indigenous representation.

Indigenous leadership opportunities

- Establish developmental initiatives, such as an Indigenous mentoring program, to advance Indigenous employees toward management positions.

- Incorporate EE goals for Indigenous people into the succession planning process. Identify and develop promising Indigenous talent; if necessary, include lower levels in the succession planning process to ensure adequate Indigenous representation.

- Recruit externally for qualified Indigenous candidates to fill senior management positions

Accommodation and corporate culture

- Provide education for management and staff on the history of Aboriginal people, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, etc.

- Train managers and supervisors on Indigenous awareness/cultural competence and on unconscious bias to avoid the influence of negative stereotypes on selection and assessment decisions.

- Be flexible in designing career paths that do not involve moving away from the home area as an accommodation for employees with community or extended family care obligations.

Accountability in meeting EE goals

- Establish accountability for managers in meeting EE goals and reinforce that accountability through regular messages from the executive level on the importance of meeting these goals.

- Ensure management, and recruiters are regularly updated on the progress in closing representation gaps at the occupational group level.

- Communicate the objectives of employment equity as distinct (though related) to those of a diversity and inclusion program so that managers do not confuse having a diverse workforce with having a fully representative workforce.

Annex B: List of participating employersFootnote 3

- Amex Bank of Canada

- Bank of America National Association, Canada Branch

- Bank of Canada

- Bank of Montreal (BMO)

- BNP Paribas

- Bridgewater Bank

- Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC)

- Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC)

- Canada Pension Plan Investment Board

- Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce

- Canadian Tire Bank

- Canadian Western Bank

- Capital One Bank (Canada Branch)

- Citibank Canada

- Equitable Bank

- Export Development Canada (EDC)

- Farm Credit Canada (FCC)

- HomeEquity Bank

- HSBC Bank Canada

- ICICI Bank Canada

- Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (Canada)

- JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A.

- KEB Hana Bank Canada

- Laurentian Bank of Canada

- Manulife Bank of Canada

- MUFG Bank, Ltd., Canada

- Branch National Bank of Canada

- Presidents Choice Bank

- Public Sector Pension Investment Board (PSP)

- Royal Bank of Canada

- State Street Bank & Trust Company - Canada Branch

- Symcor Inc.

- Tangerine Bank

- The Bank of Nova Scotia

- Toronto Dominion Bank

- Wells Fargo Bank N.A., Canadian Branch