Human rights-based approach to workplace investigations

Guidance and good practices to help federally regulated employers learn more about what is required to conduct workplace investigations in a way that respects people’s human rights and promotes a healthy and inclusive workplace.

Cat. No.: HR4-107/2023E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-68421-5

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is a workplace investigation

- When should an employer conduct a workplace investigation

- Who conducts a workplace investigation

- How to conduct a workplace investigation

- Good practices for conducting a workplace investigation

- Assess the allegations

- Consider interim measures

- Try to get it in writing

- Develop clear Terms of Reference

- Notify and support the parties

- Allow representation

- Ensure investigator independence

- Provide all relevant information to the investigator

- Ensure transparency, impartiality and the opportunity to respond

- Use investigation interviews

- Use a human rights approach to interviews

- Ensure confidentiality

- Ensure a timely investigation

- Provide regular updates

- Deliver a final investigation report

- After the investigation

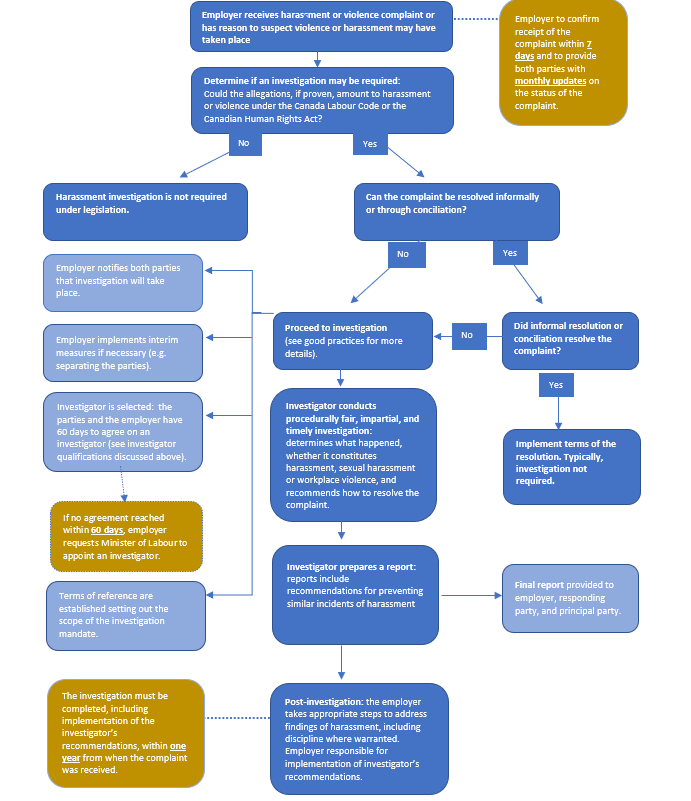

- Appendix A: Addressing Allegations of Harassment, Sexual Harassment and/or Violence Flow Chart

Introduction

Workplace harassment and violence create systemic barriers to equality in employment. They can cause significant and long-lasting psychological, emotional, and physical harm to those involved. They can profoundly impact a person’s dignity and negatively affect their ability to earn a living, to feel safe and secure, and to meaningfully take part in society. Unaddressed, workplace harassment and violence can decrease productivity and morale, and lead to increased turnover, absenteeism, and health care costs. Workplace investigations are an important way an employer can prevent and resolve issues of workplace harassment and violence. This guide will help federally regulated employers learn more about what is required to conduct workplace investigations in a way that respects people’s human rights and promotes a healthy and inclusive workplace.

An employer’s legal obligation

As of January 1st, 2021, changes to the Canada Labour Code (Code) and the supporting Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (Regulations), came into force. These changes significantly expand the legal obligations of federally regulated employers in how to handle workplace harassment and violence. Under the new Regulations, federally regulated employers are required to prevent, investigate, record, report, and provide training on workplace harassment and violence, including sexual harassment and sexual violence. All federally regulated employers must develop a workplace harassment and violence prevention policy, including direction on how harassment principal parties can be brought to the attention of the employer. Where they fail to take appropriate steps to prevent, identify and address workplace harassment and violence, employers can be held legally and financially responsible.

A federally regulated employer’s legal obligations under the Code and the Regulations go together with their obligations under the Canadian Human Right Act (CHRA). In this guide, we are referring specifically to an employer’s legal obligations to take the best steps they can to prevent and address harassment, including sexual harassment within the workplace.1 Under the CHRA, employers are required to:

- take reasonable and appropriate steps to promote compliance with the CHRA and other legislation. Employers have an obligation to foster a culture and work environment that is free from harassment and sexual harassment. This includes developing policies for the prevention of harassment, a mechanism to deal with complaints, and measures to restore the workplace following an investigation; and

- take timely and effectual steps to address harassment and sexual harassment in the workplace. This includes an obligation to investigate the allegations, to protect workers2, to prevent further incidents of harassment, and to take appropriate corrective and remedial measures when allegations of harassment are substantiated.

Good for business too

Having an effective policy in place to prevent and resolve issues of workplace harassment and violence is not only a legal requirement; it makes good business sense too. It improves the health of a workplace. A healthy workplace is one where workers feel confident that harassment or violence will not be tolerated, and where they feel comfortable and safe to speak up about these issues.

A key part of creating this type of work environment is having an effective workplace investigation process in place. The investigation process is an important tool for promoting equality and fighting discrimination. Fair and impartial investigations give workers confidence that the employer takes allegations of harassment and violence seriously and is committed to creating and maintaining a safe and respectful workplace. This is an important part of instilling a sense of confidence and safety among workers. It sends a signal across the organization that employers and unions will hold themselves accountable in relation to both their human rights obligations and their legal obligations. And that goes a long way to creating the kind workplace where good workers want to work.

Who is this guide for

This guide is intended to help federally regulated employers, workers, and unions better understand their rights and obligations when it comes to conducting workplace investigations. The recommended practices in this guide are based upon the legislative requirements under the CHRA as well as the Code.3

While many of the human rights principles presented here are universal, the specific information in this document applies to federally regulated workplaces that are governed by the CHRA and the Code. If your workplace is provincially or territorially regulated, you should consult your relevant provincial or territorial law and the resources available in the province or territory in which you work.

What is a workplace investigation

A workplace investigation is the process through which an employer examines a possible issue of workplace harassment or violence that has come to their attention. The purpose of the investigation is to gather and review information about the allegation and determine whether the harassment or violence has in fact occurred. The investigation, typically conducted by an investigator and not the employer, should also provide a thorough account of whether appropriate steps were taken by managers to address the alleged conduct leading up to the initiation of an investigation. The investigation outcome will determine what, if any, corrective and remedial steps are necessary to restore the workplace.

When should an employer conduct a workplace investigation

A workplace investigation should be conducted when:

- an employer has reason to believe workplace violence, harassment or sexual harassment may have taken place;

- there is information or allegations that could (if proven) be considered harassment or sexual harassment;

- an informal resolution process is not appropriate or was attempted but did not result in a full resolution of the matter;

- an employer receives an anonymous complaint (in writing or verbally);4 or

- an employer personally witnesses possible workplace violence or harassment. In cases such as these, employers should proactively initiate an investigation where they have reason to believe workplace violence, harassment or sexual harassment is taking (or has taken) place. Employer-initiated investigations can be an important tool in proactively identifying behaviours that may be inappropriate or discriminatory. Moreover, employers may be held legally responsible if they knew or ought to have known about harassment or violence in the workplace but do not take appropriate steps to prevent, identify, investigate, and address the behaviour.5

What is workplace harassment or violence

Not all harassment complaints will require a workplace investigation. As a first step, the employer should consider whether the allegation would meet the criteria of workplace violence or harassment under the CHRA and/or the Code. At this stage, the employer should not try to determine if the allegations are true. Rather, the employer should focus on whether the information they have (if proven) could be considered to be workplace violence or harassment under both those laws.

In the pages that follow, we will provide some working definitions of these terms, according to human rights law. But defining these terms is complex. That is why we recommend an employer also review other legislation, collective agreements, and workplace policies, which may also contain definitions of harassment, sexual harassment or workplace violence. At the end of the day, the definitions contained in federal laws take precedence and apply in all federally regulated workplaces. Workplace policies and collective agreements must be consistent with the legal definitions, but they may provide more detail or give helpful examples of what would be considered harassment, etc.

For additional guidance and definitions related to an employer’s obligations under the Code and the Regulations, please consult the following resources provided by Employment and Social Development Canada’s Labour Program:

Requirements for Employers to Prevent Harassment and Violence in Federally Regulated Workplaces. 2020. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/workplace-health-safety/harassment-violence-prevention.html

Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention (HVP) - 943-1-IPG-104 https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/laws-regulations/labour/interpretations-policies/104-harassment-violence-prevention.html

Sample Harassment and Violence Prevention Policy. 2020. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/workplace-health-safety/harassment-violence-prevention/sample-policy.html

Sample Harassment and Violence Prevention User Guide. 2020. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/workplace-health-safety/harassment-violence-prevention/sample-user-guide.html

Sample Workplace Harassment and Violence Risk Assessment Tool. 2021. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/workplace-health-safety/harassment-violence-prevention/risk-assessment-tool.html

What is Harassment

Harassment in any form has a harmful impact on a workplace. When it is linked to one or more of the prohibited grounds listed in the CHRA it is also a serious form of discrimination.6 Harassment creates systemic barriers to equality in employment. Employers must take steps to ensure their workplace is free from harassment. Where they fail to take appropriate steps to prevent, identify and address workplace harassment, employers can be held legally and financially responsible.

Harassment is when someone says or does something that offends or humiliates another person. Usually, the harasser must say or do these offensive things many times, but a serious one-time incident may also be harassment.7 Harassment can be direct or indirect, obvious or subtle, physical or psychological. It can occur in many ways, such as through spoken words, text, gestures, and images.

Even if an individual did not harass someone on purpose (with intent), their behaviour can still be harassment. The question is whether a reasonable person would have known that the behaviour in question was unwelcome.

Examples of workplace harassment include, but are not limited to:

- creating a toxic work environment (e.g. tolerating hostile, insulting or degrading comments or conduct)

- spreading rumours or gossip about an individual or group

- making offensive jokes or remarks

- cyber bullying (threatening, spreading rumours or talking negatively about an individual online)

- threats made in person, by phone, email, or through another medium to a worker (including from individuals unassociated with the workplace, such as a spouse or family member, when the incident occurs during the course of work and/or affects the safety of the workplace)

- playing unwanted practical jokes

- socially excluding or isolating someone

- stalking or inappropriately following a person

- tampering with someone’s work equipment or personal belongings

- vandalizing or hiding personal belongings or work equipment

- impeding a person’s work in any deliberate way

- persistently criticizing, undermining, belittling, demeaning or ridiculing a person

- intruding on a person’s privacy

- public ridicule or discipline

- unwelcome physical contact

- sexual innuendo or insinuation

- unwanted and inappropriate invitations or requests, including of a sexual nature

- displaying or sharing offensive posters, cartoons, images or other visuals

- making aggressive, threatening or rude gestures

- misusing authority, including:

- Constantly changing work guidelines

- Restricting information

- Setting impossible deadlines that lead to failure, and/or

- Blocking applications for leave, training or promoting in an arbitrary manner

- microaggressions, or subtle acts of exclusion.

Microaggressions are brief, indirect, and everyday slights, indignities, put-downs, and insults that communicate discriminatory attitudes towards members of equity-deserving groups. These can be behavioural, verbal, or environmental, and can be intentional or unintentional. Microaggressions can leave those subjected to them feeling uncomfortable, unwelcome, insulted, othered, and painfully reminded of stereotypes associated to their identities. Examples of racist microaggressions include, among many others, insistently asking a racialized person where they are really from, complimenting a racialized person on the quality of their English, or clutching one’s bag tighter in the presence of a Black man. Sexist and/or gendered microaggressions can reinforce traditional gender roles in the workplace, including masculine privilege and dominance. These may come in the form of comments on a woman’s appearance, demeaning comments about a woman’s abilities, and assumptions of inferiority of women in certain fields. These are all examples that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes towards women. While there may be no harm consciously intended, microaggressions nevertheless cause harm, and the harmful impact is cumulative as those affected people experience these microaggressions frequently in their day-to-day lives.

Both the CHRA and the Code protect workers in the workplace.

The CHRA prohibits harassment in employment and in the provision of services based on one or a combination of the 13 prohibited grounds of discrimination.

The Code also protects workers from harassment, including harassment that is not linked to a prohibited ground, such as domestic violence. The Code defines harassment and violence at subsection 122(1):

Harassment and violence is any action, conduct or comment, including of a sexual nature that can reasonably be expected to cause offence, humiliation or other physical or psychological injury or illness to [a worker], including any prescribed action, conduct or comment.

Workplace harassment does not include appropriate management action (such as performance evaluations, directives and job assignments) if these are carried out in a fair manner and for legitimate reasons. However, management action that results in a negative impact, and which is made based on a prohibited ground, can constitute harassment and/or discrimination. For example, it is a discriminatory practice if a person’s race is a factor in a manager’s decision to assign a less desirable task or shift to them.

What is Sexual harassment

While sexual harassment is not thoroughly defined in the CHRA, it is broadly defined as unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that is likely to cause offence or humiliation to a worker. It is a demeaning practice that violates the dignity and self-respect of the victim, both as a worker and as a human being.

Sexual harassment can take many forms and may target any gender, including men, women, trans, non-binary and gender-diverse individuals.

Examples of sexual harassment include, but are not limited to:

- unnecessary or unwanted physical contact

- persistent questions, insinuations or spreading gossip about a person’s private life such as their sexuality, gender identity or expression or sex life

- insults or demeaning comments about one’s gender or gender role

- staring at a person or parts of their body

- treating an individual differently because they do not conform to the gender role which one expects, such as a role that has been traditionally occupied by another gender

- repeated invitations to go out after prior refusal

- sexually explicit comments or gender-based jokes

- displaying or circulating offensive graphics, drawings, e-mails, text messages, letters, or comments

- making promises or threats in return for sexual favours

- the creation or perpetuation of a poisoned environment, where workers must tolerate or endure generalized sexual or gender related ridicule as part of a workplace culture

- any other behaviour that could reasonably be thought to put sexual conditions on a person’s job or employment opportunities

What is a poisoned work environment

The concept of the poisoned environment is closely linked with the concept of discriminatory harassment, and is systemic in nature. A poisoned work environment is one in which insulting or degrading comments, actions or microaggressions cause individuals or groups to feel that the workplace is hostile or unwelcoming. When comments or conduct of this kind have an influence on others and how they are treated, this is known as a poisoned environment.

The essential feature of a poisoned work environment is that it is experienced by or impacts on more than just one individual such that it can be considered a practice, and has a detrimental effect on employment opportunities, particularly for those workers with the shared characteristics targeted by the conduct.

What is workplace violence

Federal labour law defines workplace violence as actions, conduct, threats or gestures that can be reasonably expected to cause harm, injury or illness. Violence can include, but is not limited to, the following acts or attempted acts:

- verbal threats or intimidation

- verbal abuse, including swearing or shouting offensively at a person

- contact of a sexual nature

- contact, other than accidental, of any nature, including kicking, spitting, punching, scratching, biting, squeezing, pinching, battering, hitting or wounding a person in any way

- attacking or threatening to attack someone with any type of weapon

Intent is irrelevant in establishing finding of harassment

An Indigenous worker alleged that he was harassed by racist comments, jokes, and names from his supervisors and colleagues. Some of the witnesses claimed that although such jokes or comments were made, they were made in the spirit of fun between friends, and that no offense was meant. The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (the Tribunal) found that the intent of the comments is irrelevant: “The issue is the perception of the individual who is victimized.”

The fact that the victim did not object to the comments and even participated in the “joking” was raised as a defense. The Tribunal held that this did not mean that the victim had consented to the racist comments, jokes and names or made this behaviour acceptable. According to the testimony of an expert witness, people may go along with activities “that they find objectionable and demeaning because they feel powerless to stop it and as an ego defense mechanism”…it is “a form of coping.” (Swan v. Canadian Armed Forces)

Should you try informal resolution first

Before initiating the investigation process, it is helpful to consider whether the matter can be resolved informally between the persons concerned. An early or informal resolution of a complaint may not always be appropriate or possible. This will depend on a number of factors:

- How the principal party8 would like the matter to be handled. The principal party is the technical term in federal labour law for the person who made the allegation. (In human rights law they are referred to as the complainant). It also matters how the responding party (the person alleged to have committed harassment or violence, or respondent) would like the matter to be handled. It is critical to respect the needs of both parties and ensure that the investigation and/or informal resolution process does not harm their dignity and self-respect. For example, where the principal party is experiencing trauma because of the responding party’s alleged behaviour, informal resolution may be inappropriate.

- Whether there is a power imbalance between the principal party and the responding party. A power imbalance can occur, for example, when the responding party is the principal party’s supervisor or has the ability to influence their work or their career progression. This could include where the principal party is a vulnerable worker, such as an intern or a temporary, new or probationary worker. In these circumstances, a principal party may not feel they can meaningfully participate in an informal resolution process because, for example, they fear reprisals or feel it is unsafe to raise concerns about the responding party in this way.

- The employer’s understanding of the circumstances, including the nature and seriousness of the allegations. For example, an informal resolution will not be appropriate if the responding party’s alleged behaviour seems to be widespread, systemic or to involve serious allegations, such as unwelcome sexual contact or threatening behaviour. The purpose of an informal resolution process is to address specific individual concerns so that relationships can be restored or maintained and the principal party can continue to flourish safely at work. It is not a process intended to mitigate the need to address larger systemic issues.

Where appropriate, informal resolution can provide an opportunity to resolve a dispute in a mutually respectful manner, while preventing an escalation of the situation. Informal resolution can involve a range of options, including a meeting between the principal party and the responding party, and a manager or supervisor. It can also involve a meeting with a third party (such as a facilitator, mediator or conciliator),9 who helps both parties arrive at a resolution that works for everyone. Both parties must agree on using a third party and who precisely that will be.10

Who conducts a workplace investigation

Finding an investigator

It is a best practice for an employer to seek the expertise of an impartial investigator. Investigators should be selected using a collaborative process.11 The employer, the principal party, and the responding party should attempt to agree on the selection of a qualified investigator.

In advance of a situation where an investigator needs to be appointed, employers should consider working with the organization’s “applicable partner”12 to develop a mutually agreed-to list of qualified investigators to have at the ready.13

In the absence of an established list, and if there is no agreement on the appointment of an investigator within 60 days of the notice of investigation, the employer must appoint “a person from among those whom the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety identifies as having the knowledge, training and experience referred to in subsection 28(1) of the regulations.”14

Key qualifications of a good investigator

According to the Code, a workplace investigator should have the following qualifications:

- training and experience in investigative techniques (in some circumstances, it will be important that the investigator have experience conducting trauma-informed investigations)

- knowledge, training, and experience that is relevant to various forms of harassment and violence in the workplace, including an understanding of microaggressions in the context of employment

- where necessary, knowledge, training and experience related to substantive equality, racism, gender-bias, colonization, unconscious biases, trauma-theory, gender-based violence, and/or systemic discrimination

- knowledge and experience applying the CHRA and other principles and legislation relevant to harassment and violence in the workplace15

The investigator must also be impartial and have no direct involvement with the matter under investigation. The investigator must be in a position to consider the allegations with an open mind. For example, the investigator must not report to or supervise the principal party or the responding party.

The investigator may be external to the organization, for example, a lawyer or human resources professional who is retained to conduct the investigation. The investigator may also be an in-house worker, such as a member of the human resources department or in-house counsel. Whether they are external or internal to the employer organization, all investigators must have the qualifications set out above.

A number of factors may help determine whether an internal or external investigator should be selected. For example:

- Is an in-house worker qualified to conduct the investigation?

- Is the in-house worker sufficiently removed from the incident(s) or work unit in which the allegations occurred? Do they report to or supervise any of the parties?

- Does the investigation involve alleged conduct by senior management? If so, it may be necessary to engage an external investigator.

- Are the allegations complex, serious, or extensive? While there is no legal requirement to engage an external investigator simply because the circumstances are complex or serious, it may be advisable to do so. An experienced, external investigator may be better equipped than an in-house worker to navigate complex investigations. Their independence from the organization may also add to the parties’ perception of the fairness and objectivity of the investigation.

How to conduct a workplace investigation

How it works

An investigator will begin by gathering information that is relevant to the investigation mandate. This will include reviewing any workplace policy as well as any written complaint(s) and response(s).

The investigator will then meet separately with the persons involved, including both parties and anyone who may have witnessed events or have relevant information (a “witness”). The investigator may also obtain and review documents or other information that is relevant to the allegations or the response.

The investigator’s role is to consider this information and determine:

- what happened;

- whether it amounts to harassment or sexual harassment within the meaning of the CHRA, the Code and/or a workplace policy or applicable collective agreement; and

- if so, what are the appropriate remedial measures?

Investigations are not always conducted in the same way and do not always follow the same course. For example, some investigators will begin by meeting with the principal party, while others will begin by meeting with the responding party. There is no single correct way to conduct an investigation and the investigator’s approach may vary depending on the types of allegations, the circumstances of the parties, and the information available.

Guiding principles

Importantly, regardless of how it is conducted, any investigation must be conducted according to the following principles of procedural fairness:

Impartiality

The investigator must not have a personal stake in the outcome of the investigation. They should make their conclusions based on an unbiased assessment of the information available to them. An investigator must not only be impartial, but must also appear impartial. The parties involved must have no doubt in their mind of the independence of the investigator. The perception of bias can have a chilling effect on participation in an investigation if any of the parties or witnesses perceive the investigator as representing the interests of anyone in particular.

Transparency

Transparency means conducting the investigation in an open and visible manner. It means letting others see what actions the investigator is taking. Both parties must be aware that they each will receive and have an opportunity to respond to all of the information being made available to the investigator.

The investigator must share relevant documents and information with both parties. The investigator should also give the parties an opportunity to propose witnesses and provide documents. The investigator should share with the parties any relevant information received from the employer, the other party or witnesses. The investigator’s obligation to be fully transparent continues throughout the investigation process. For example, if (after meeting with the parties) the investigator receives a new piece of relevant information, they must disclose that information to both parties and give them an opportunity to respond or comment.

Timeliness

Time matters in an investigation. Employers have an obligation to ensure that the investigation process occurs promptly and without avoidable delays.

Investigators must also ensure the investigation is conducted in as timely a manner as possible. A lengthy investigation can give rise to prolonged tension in the workplace as well as lost evidence and vague memories. Of course, timeliness will depend on the circumstances, including the number and availability of witnesses, the complexity of the issues, and the number of factual issues in dispute.

It is also important to note that statutory time limits may vary. That is why employers must ensure that investigations respect the timeframes established by the law under which their investigation is being conducted.

Thoroughness

In a formal investigation process, thoroughness does not have precisely the same meaning as it does in our daily use of the term. While an investigation must be thorough, it should not exceed the terms of reference for the investigation. For example, thoroughness does not require that the investigator interview a witness if the information suggests that the individual would not have any direct knowledge of issues relevant to the allegations. In other words, thoroughness does not require that an investigator turn over every stone. It only requires the investigator to turn over stones that might cover information pertinent to the allegations.

The investigation must also be conducted in a manner that is consistent with the Code, its Regulations and any workplace policy or collective agreement provisions.

Good practices for conducting a workplace investigation

Although there is no specific formula for conducting an investigation, there are a number of recommended good practices outlined in the Code:

1. Assess the allegations

When an allegation is brought forward, the employer must assess whether it contains enough information/details to be considered workplace violence or harassment as defined in the Code and/or the CHRA. At a minimum, the complaint must include:

- a description of the incident(s) and, if relevant, whether the treatment is linked to a prohibited ground of discrimination

- name(s) of alleged perpetrator of violence or harassment (responding party)

- date(s), time(s) and location(s) of incidents

An employer is not required to investigate “bald allegations.” A bald allegation is one that does not contain sufficient detail to meet the definition of workplace violence or harassment (e.g. My supervisor is harassing me everyday at work because he does not like people who practice my religion.) However, if such an allegation is received, it is a good practice to ask the worker for additional supporting details before assessing whether the complaint warrants further investigation.

2. Consider interim measures

Depending on the nature of the allegations and the persons involved, it may be necessary for the employer to take interim measures even before they have an outcome of the investigation. For example, in some circumstances, the principal party and the responding party should not be in contact with each other until the investigation has concluded. The employer may also need to prevent the responding party from having contact with others.

It is important that interim measures do not penalize a principal party for raising allegations. Therefore, where it is appropriate to separate the principal party and the responding party, it is a good practice not to change the principal party’s working conditions unless it is their expressed preference. However, the interim measures are not intended to penalize the responding party. Interim measures should be limited to what is absolutely necessary to ensure that workers are protected from the conditions in which the alleged incident took place.

Other examples of interim measures include: placing the responding party on paid administrative leave; directing the responding party to work from home; or reassigning the responding party to appropriate tasks that do not involve contact with the principal party.

3. Try to get it in writing

It is important to note that there is no requirement in the Code that allegations must be made in writing. But wherever possible, it is a good practice to invite the principal party to prepare a written complaint. A written complaint can be helpful as it clearly establishes the nature of the allegations, which then form a basis for determining the scope of the investigation and the investigator’s mandate. A written complaint may not be practical in every instance, for example, where a principal party is reluctant to prepare a written document or where his or her literacy level makes that difficult. But as already mentioned in this guide, allegations can also be verbal and an employer may be required to investigate complaints that are made verbally.16

Where a written complaint is received, that document should be shared with the responding party before the investigator meets with them. The responding party should be given a reasonable opportunity to respond in writing to the written complaint. Their written response should be shared with the principal party before the investigator meets with him/her. The principal party should also have an opportunity to respond a final time to the written document. All of this may be done in writing or verbally during an interview.

4. Develop clear Terms of Reference

Terms of Reference are typically an agreement between the employer and the investigator that defines the scope of the investigation (also referred to as the investigation mandate). Terms of Reference should be created for internal and external investigations. In both cases, a clear mandate is critical to keep an investigation focussed and to ensure procedural fairness.

Federal Court affirms need for clear mandate

In Shoan v. Canada (Attorney General), 2016 FC 1003 (CanLII), the Federal Court found that an investigator violated principles of procedural fairness by exceeding the scope of her investigation mandate, which was to investigate email correspondence and conduct between the principal party and the responding party. The Court found that the investigator had considered and made findings regarding the responding party’s conduct toward other individuals at various social and work events, which went beyond the scope of her mandate. This was considered a breach of procedural fairness. Because of this breach, the Court set aside the investigator’s report and the corrective measures that the employer had imposed on the responding party.

In developing the Terms of Reference, it is important that the parameters of an investigation be broad enough to address the complaint or concerns that have been raised. However, if the allegation is overly broad or spans multiple years, this may require a more involved investigation and may raise issues of procedural fairness (e.g. the availability of witnesses and their ability to recollect incidents.).

The investigator must address all of the allegations contained in the Terms of Reference, but they may not address issues that are not part of the Terms of Reference. This does not, however, prevent the investigator from receiving and considering information that provides relevant context to the allegations. As a good practice, should the investigator become aware of other allegations, he or she should contact the employer and seek instructions about whether the Terms of Reference will be amended to include these new allegations.

In addition to setting out the scope of the investigation, the Terms of Reference should include:

- The precise allegations or issues under investigation. For example, an investigation may set out to investigate the precise allegations raised in a written complaint filed by a particular worker on a particular date.

- A statement that the investigation will adhere to the applicable statutes, agreements and policies, including (as applicable) the CHRA, the Code, and the Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations and applicable case law. The investigator should also adhere to any applicable collective agreement.

- A requirement that the investigation is conducted in a fair and impartial manner by an independent investigator.

- A requirement that all information obtained during the investigation remain confidential to the extent possible.

- Requirements regarding document retention. While the investigation report is shared with the parties, the investigator generally retains their notes as well as other documents related to the investigation. In very limited circumstances, some of these documents can be considered privileged (e.g. legal advice exchanged between client and counsel). In most circumstances, however, a court, tribunal or arbitrator will require that they be produced (or shared) as part of the adjudication process.

- The cost of the investigation and terms for their payment, in cases that engage an external investigator.

As a good practice, the Terms of Reference should be shared with both parties, though the cost of the external investigator doesn’t necessarily have to be.

5. Notify and support the parties

The employer must notify the principal party and the responding party that an investigation is being initiated.17 Participating in an investigation is a stressful experience, and employers should be mindful of this in their communications with the parties. Employers are required to support workers affected by harassment, sexual harassment, and violence in the workplace.18 The principal party and the responding party should be given as much information as possible about the investigation process and, as a good practice, should be reminded of resources that are available to assist them, including Employee Assistance Programs where available. The parties should also be reassured that the investigation is a confidential process and that they are entitled to be represented throughout the investigation.

6. Allow representation

The principal party and the responding party are entitled to be accompanied or represented at any stage of the investigation process.19 Where a party is a member of a union, they may choose to be represented by their union.

Investigators must advise the parties of their right to representation. If a party wishes to be represented, the investigator should not interview them without their representative present. Doing so may call into question the investigation process and any findings or recommendations that flow from it.

In some instances, a party may wish to be accompanied by someone who will provide moral support rather than active representation. It is a good practice to permit witnesses to have a support person during interviews with the investigator. This may alleviate some of the stress and discomfort inherent to investigation interviews, and have a positive effect on the process. As another good practice, the investigator should advise the parties of their right to be accompanied by a support person during the investigation process.

7. Ensure investigator independence

As previously mentioned, the investigation should be conducted in a manner that is totally independent. This means that they do not take instructions from the employer or the parties regarding how the investigation is conducted (who to interview, what documents to review, in what order to do so) or what conclusions are reached. The investigator should gather the information they feel is necessary and should then determine the issues based on their own evaluation of that information.

8. Provide all relevant information to the investigator

Employers should provide the investigator with a copy of any workplace policy and applicable collective agreement as well as any written complaint and response. The employer should indicate that any further relevant information will be provided upon request from the investigator.

The Code requires an employer to provide the investigator with “all information that is relevant to the investigation.”20

9. Ensure transparency, impartiality and the opportunity to respond

As mentioned under Guiding principles, procedural fairness requires that the investigator openly share all relevant documents and information with both parties. The investigator should also give parties an opportunity to propose witnesses and provide documents. The investigator should share with the parties any relevant information or documents received from the employer, the other party or witnesses.

The investigator’s obligation to share relevant information continues throughout the investigation process. For example, if after meeting with the parties the investigator receives new relevant information, they must share that information with both parties and give them an opportunity to respond or comment. This may be achieved in a variety of ways. For example, the investigator can:

- conduct a follow-up interview with one or both of the parties to discuss new or additional information;

- share information or documents with each of the parties in writing and invite written comments from them; or

- prepare a preliminary report, which summarizes the investigator’s findings. The parties may be given an opportunity to provide written comments before the document is finalized and shared with the employer.

This list is not exhaustive. Investigators may take these or other steps to ensure transparency and impartiality.

10. Use investigation interviews

The purpose of an investigation interview is to gather information about the allegation, the nature of the incident, the response, and the circumstances under which this all took place. The interview may also give the parties an opportunity to understand and respond to relevant information the investigator has received. Investigators should communicate with the parties and witnesses before the interview to explain the investigation process and scope, the role of the investigator, and the participants’ obligation to maintain confidentiality. Before meeting with them, investigators should also share any relevant documents they have received with the parties.

As previously noted, the investigator must be impartial, including during the investigation interviews. The investigator should not make comments or ask questions in a way that suggests they have already made a conclusion about what happened.21

Who should be interviewed

Deciding who to interview is important. Investigators must be thorough, but they must also stay within the scope of their mandate and avoid letting the investigation go on any longer than it must (e.g. interviewing witnesses who do not appear to have new or relevant information to contribute.).

Investigators should interview both parties. They may also interview other witnesses. Typically, the investigator should select witnesses who have first-hand information (something they themselves saw or heard) that is relevant to allegation. Witnesses are often objective observers and the information they provide can be very helpful to the investigation, particularly where there is a factual dispute between the parties.

In selecting which witnesses to interview, the investigator should be mindful of the extent of a witness’s objectivity. A witness who does not have a personal or reporting relationship to the parties may be preferred over someone who is a friend or subordinate of one or both of the parties.

As part of their role, the investigator will typically identify some witnesses, while also giving the parties an opportunity to propose their own witnesses. The investigator should ask the parties to explain why they feel the particular individual has information that is relevant to the investigation. However, the investigator ultimately determines who to interview, and they should advise the parties that this may or may not include their proposed witnesses.

The order in which interviews are conducted

The order in which the interviews are conducted may vary. Regardless of the order in which interviews are conducted, the parties must have an opportunity to know and respond to the relevant information.

In some circumstances, it may be appropriate for the investigator to meet with the parties more than once.

11. Use a human rights approach to interviews

The investigator should ensure that investigation interviews are conducted in a private, convenient, and neutral location. It is often helpful to hold the interviews outside of the workplace unless there is a quiet, private location at work that is acceptable to all participants. As much as possible, the investigator should schedule interviews at a time and in a manner that avoids disrupting the workplace or the participants.

Importantly, investigators must accommodate the participants’ human rights-related needs and ensure that the interview be held at a location that is accessible to them. For example, if a party or witness is on a disability-related leave from the workplace, the investigator should ensure that they are medically able to participate in the investigation before interviewing them. The investigator should ensure that interpretation or alternative accessible locations are made available as required. The employer typically bears the reasonable cost of providing such services.

If conducting consecutive interviews, investigators should avoid a situation where the parties or the witnesses will encounter each other. This is important for privacy and confidentiality, and also because such encounters may be unwanted or uncomfortable.

The investigator should take notes during the interviews. Depending on the investigator’s style as well as the nature of the case, some investigators will ask each participant to review those notes, make corrections, and sign them to confirm that they agree with the information. While the investigator is not legally required to share interview notes with the parties, the parties must have an opportunity to respond to relevant information obtained throughout the process (see Good Practice #8 above).

The investigator and/or a participant may also wish to record the interview. The participants should have an opportunity to agree or disagree to this prior to the interview. Any recording of the interview is confidential and is covered by the confidentiality agreement everyone has signed (see below). As a good practice, the investigator should request that the participant provide a copy of the recording as well as any transcription of the recording to the investigator.

12. Ensure confidentiality

Confidentiality agreements

The investigation must be conducted in a manner that is as confidential as possible. All participants in the investigation have confidentiality rights and obligations. The investigator should urge the parties, witnesses, and their representatives or support persons to sign a confidentiality agreement. The investigator should advise the participants of their confidentiality obligations. The investigator should also provide a copy of the confidentiality agreement before meeting with participants or sharing documents or information with them.

The purpose of the confidentiality agreement is to: (a) ensure the privacy of the participants while the investigation is being conducted (and before any outcome has been reached); and (b) protect the integrity of information and ensure that participants do not compare information before providing evidence to the investigator. Confidentiality agreements should be worded carefully and their scope should be limited to what is strictly necessary to achieve these two objectives.

Confidentiality agreements should:

- be limited to the duration of the investigation. They should not prevent participants from making statements once the investigation is complete;

- not prevent persons from seeking counseling, treatment or support during or after the investigation;

- not prevent principal parties or witnesses from sharing information necessary to protect others from harassment, sexual harassment, and violence;

- not prevent principal parties or witnesses from reporting past, current or future harassment or violence;

- not prevent the disclosure of information necessary to advance any other legal proceedings (civil, criminal, administrative) arising from the same circumstances; and,

- not interfere with employers’ ability to identify and deal effectively with systemic issues or patterns of behaviour, including repeated or ongoing harassment or violence by a responding party or responding parties.

In this context, confidentiality agreements are generally different from what are typically referred to as “non-disclosure agreements” or NDAs. An NDA typically refers to a provision within a settlement agreement between a principal party and an alleged responding party.

Non-disclosure agreements

The use of NDAs to settle harassment complaints has been highly criticized. NDAs often have no expiry date, and their purpose is generally to keep the terms and existence of a settlement agreement secret. Depending on how they are worded, NDAs can limit the principal party’s ability to discuss with anyone their allegations, the information related to the allegations, the content of the settlement agreement, and the fact that a settlement was reached. If implemented without careful consideration of their potential negative impact, NDAs may operate to conceal incidents of repeated harassment, sexual harassment or violence. They may also prevent organizations from adequately addressing systemic or repeated issues. Some NDAs even try to limit a person’s ability to access treatment, counseling or other support services. NDAs are highly discouraged unless the principal party has access to adequate legal representation and/or advocacy.

Witnesses and confidentiality

As stated in the Regulations under the Code, the identity of witnesses should not be disclosed directly or indirectly in the investigator’s report. It is also important that the investigator not disclose the names of witnesses throughout the investigation in general, to the best of their ability.22 Participating in an investigation can be stressful for witnesses and it may place them in a vulnerable position. Protecting the identity of witnesses is a good way to reassure those who might be reluctant to come forward or who may fear reprisal.

Neither party is legally entitled to know the identity of witnesses, nor be offered access to the investigator’s interview notes with witnesses.23 However, the parties are entitled to know and respond to the substance of the relevant information received from witness interviews.

13. Ensure a timely investigation

Under the CHRA, employers are required to prevent and address harassment and violence in the workplace. This includes responding to harassment and violence allegations effectively and in a timely manner. Given these obligations, employers have an important role to play in ensuring that the investigation process occurs promptly and without avoidable delays.

Investigators must also ensure the investigation is conducted in as timely a manner as possible. A lengthy investigation can give rise to prolonged tension in the workplace as well as lost evidence and vague memories. What is timely will depend on the circumstances, including the number and availability of witnesses, the complexity of the issues, and the number of factual issues in dispute.

In the Regulations under the Code, there is a one-year limit for concluding the investigation, including the employer’s implementation of recommendations contained in the investigator’s reports. The one-year limit begins from the day on which the employer is notified of the occurrence.24 Where a collective agreement or workplace policy contains timeframes for investigations, these must be respected as long as they do not exceed the time limits set out in the Regulations. Importantly, however, these timelines should serve as minimum requirements. Investigators should strive to complete investigations in a timely manner and well in advance of the one-year limit contained in the Regulations.

14. Provide regular updates

Throughout the investigation process, the investigator must provide regular updates to the parties and the employer. These updates should include information about the progress of the investigation, including the next steps and (where possible) the expected timeframes. The Regulations also require the employer to provide monthly updates on the status of a complaint to both the principal party and the responding party.25 If an investigation is underway, the employer can work with the investigator to compile the information for those updates.

The employer’s obligation to provide monthly updates ends when the investigator has provided the final and summary reports to the employer (discussed below) and the employer has implemented the recommendations adopted in tandem with the applicable partner.26

15. Deliver a final investigation report

Once the investigator has gathered the evidence, they must prepare a final written report. They must provide their final report to the employer, the principal party, and the responding party.

The final report must include a detailed description of the incident, the investigator’s conclusions and recommendations to eliminate or minimize the risk of a similar incidents reoccurring. This report must not disclose, directly or indirectly, the identity of any witness or third party.27

In preparing the investigation report, investigators should:

- address all of the principal party’s allegations;

- only make findings about matters that are within the investigation mandate;

- clearly explain the rationale for those findings;

- explain why one party's version is preferred over another’s when there are different versions of relevant facts;

- consider the following when assessing the credibility and reliability of evidence:

- the believability of a witness or party’s version of events

- the consistency of the information provided by the parties

- any inconsistencies between witness accounts and documentary evidence

- the manner in which the witness or party provides information

- the relationship of a witness to the parties;

- explain why certain witnesses proposed by one of the parties were not interviewed. Such situations may include:

- the witness did not appear to have any direct knowledge of the issues in dispute.

- the witness did not respond to the investigator’s invitation to meet; and,

- describe any procedural issues or objections regarding the investigation process, and explain how they were addressed. For example, if a party argues they did not have the opportunity to respond to certain information, the report should describe what information was provided and why the investigator believes it was sufficient.

In providing recommendations to eliminate or minimize the risk of a similar incident recurring, investigators should be mindful of the limitations of both their role and the information available to them. For example, an investigator should refrain from recommending specific disciplinary measures, particularly when unaware of a party’s full disciplinary history. It is most useful for the investigator to make general recommendations that can be applied by the employer based on the specific context and conditions of employment.

After the investigation

Measures to address workplace harassment

The Regulations state that the employer and the “applicable partner” must jointly determine which of the recommendations included in the investigator’s report should be implemented.28 The employer is responsible for implementing these recommendations.29

In addition, as per section 65 of the CHRA, any harassment or discriminatory act committed by a worker is considered to be an act committed by the employer, unless the employer can demonstrate that it “exercised all due diligence to prevent the act” and took measures to address the impact and remediate any resulting harm.30

Record keeping and review

Under the Regulations, the employer is required to keep a record of each workplace harassment or violence complaint, how it responded to that complaint, and a copy of the investigation report for a period of ten years.31

These records provide valuable insight into workplace violence harassment and perceived harassment in the workplace. Employers should review these records on a regular basis to look for patterns, such as repeated or multiple harassment complaints in certain departments or complaints dealing with specific persons. Monitoring these records and taking appropriate action to address underlying issues is part of an employer’s duty to prevent harassment in the workplace, and may limit liability for incidents in the workplace as per section 65(2) of the CHRA.

Employers should also be aware of their obligation under the Code to compile information on harassment complaints and provide these records annually in a report to the Minister of Labour, or the designated Head of Compliance and Enforcement.32

As a good practice, investigators should also keep their investigation records, such as notes, transcriptions, and other documents, for a period of 10 years.33

Appendix A: Addressing Allegations of Harassment, Sexual Harassment and/or Violence Flow Chart

Text version

The graphic is a Flow Chart about the process for addressing an allegation of harassment, sexual harassment and/or violence. The first step described in a text box says: Employer receives harassment complaint or has reason to suspect harassment may have taken place.

There is another text box to the right connected to the first box with a dotted line. It says: Employer to confirm receipt of the complaint within 7 days and to provide both parties with monthly updates on the status of the complaint.

Under the first step is an arrow pointing to the next step, which is described in a text box that says: Determine if an investigation may be required - Could the allegations, if proven, amount to harassment under the Canada Labour Code or the Canadian Human Rights Act?.

There are two arrows flowing from this box to either “No” or “Yes”. There is an arrow pointing down from the “No” box to another text box that says: Harassment investigation is not required under legislation.

There is an arrow pointing down from the “Yes” box to another text box that says: Can the complaint be resolved informally or through conciliation?

There are two arrows flowing from this box to either “No” or “Yes”.

There is an arrow pointing down from the “Yes” box to another text box that says: Did informal resolution or conciliation resolve the complaint?

If the answer is yes, there is an arrow down to a text box that says: Implement terms of the resolution. Typically, investigation not required.

If the answer is no, an arrow points to a text box that says: Proceed to investigation (see good practices for more details).

If the complaint cannot be resolved informally, there is an arrow pointing down from a “No” box to the text box that says: Proceed to investigation (see good practices for ore details). From this box there are arrows pointing to four separate text boxes. The first box says: Employer notifies both parties that investigation will take place. The second box says: Employer implements interim measures if necessary (e.g. separating the parties). The third box says: Investigator is selected – the parties and the employer have 60 days to agree an investigator (see investigator qualifications discussed above). There is an arrow from the third box to another text box that says: If no agreement reached within 60 days, employer requests Minister of Labour to appoint an investigator. The fourth box says: Terms of reference are established setting out the scope of the investigation mandate.

From the text box that says Proceed to investigation, there is also an arrow that points down to a text box that says: Investigator conducts fair, impartial, and timely investigation - determines what happened, whether it constitutes harassment, sexual harassment or workplace violence, and recommends how to resolve the complaint.

Under this text box, there is an arrow pointing down to a text box that says: Investigator prepares a report - reports include recommendations for preventing similar incidents of harassment. From this text box there is an arrow pointing right to a text box that says: Final report provided to employer, responding party, and principal party.

From the text box that says Investigator prepares a report, there is another arrow pointing down to a text box that says: Post-investigation - the employer takes appropriate steps to address findings of harassment, including discipline where warranted. Employer responsible for implementation of investigator’s recommendations.

A dotted line connects this last text box to a text box on the left that says: The investigation must be completed, including implementation of the investigator’s recommendations, within one year from when the complaint was received.